(turn sound on)

The AI Sound House

A General Theory of Bangers

The AI Sound House

Prelude

I found a song I really liked. I played it 10,000 times. Then I didn't like it anymore.

I: Music, the Field Guide

There's an episode of The Young Pope where Jude Law, playing a pope who is young, asks:

I keep on coming back to that distinction. It turns out to be useful for all sorts of things, music included. Maybe especially music. Because: Is there a most important music? A best music? What would the criteria even be? What is music, come to think of it, is that obvious to everyone?

Consider John Cage's 4'33 or As Slow As Possible whose adaptation is set to end in 2640, or Mieko-Chieko's boundary music . Hmm, not so clear then. Okay, so let's agree that music is sound that has been put together with some goal and can make you feel something.

Now, most music is forgettable, let alone important. A great deal of it is bad. As our capacity to produce sound approaches infinity, as we drift toward something like the Music Library of Babel, we should expect the ratio to worsen. More good music, yes, but a lot more bad music. The good will remain what it has always been: the tiny fraction that makes certain neurons hold hands and skip rope. The bad will be everything else, which is nearly all of it, which is fine. Now, the Library is infinite and your life is not, so the real question, the one that keeps a certain type of person up at night, is: will we find all this good? And is there some way to make it easier to find?

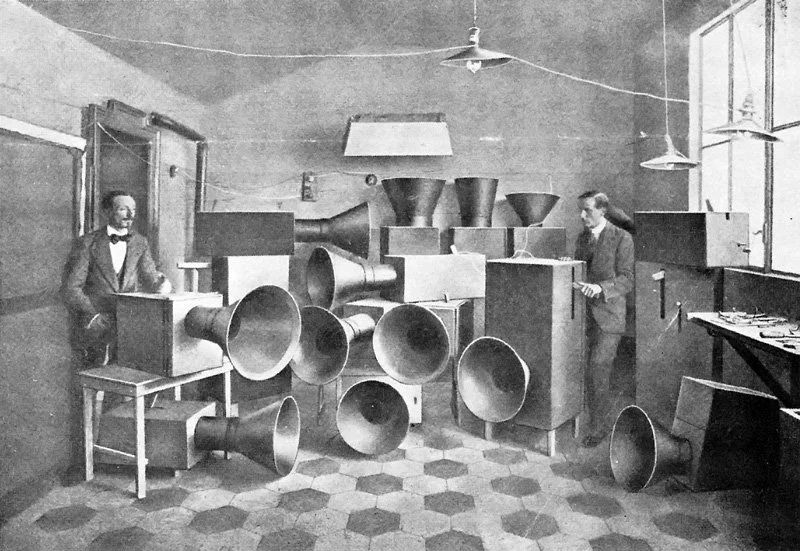

The ordinary amazing thing is that there's a pathway from sound to feeling. I like the 1932 perspective of conductor Leopold Stokowski:

There is a receiving set in the house of some music lovers. They sit and listen to the music. The receiving set gives out as many frequencies and as much intensity as the company and the radio commission permits (laughter) and perhaps they will give you some more later. The air in that room vibrates. It strikes here (indicating the ear). It is conveyed to the brain. It is transformed from air vibration into some other kind of vibration of which we know little. And then comes a miracle. It evokes states of feeling and states of being which are so powerful that one almost loses control of one's self–states of feeling that are so inspiring, that make one see visions of beauty, possibilities in life, that in ordinary every-day life don't exist for us. And yet we are the same persons. It is just a little air vibration which creates this miracle and we become inspired. Why is that? We know so little, but we ought to know. Physicists, musicians, we who are trying to do this wonderful thing, we should know that ultimate limit there. We should understand what this extraordinary circuit is from inspiration through transmission, through reception, back to inspiration.

We don't need to understand the whole process to know that it works. This means we can build tools to explore the space of feelings with music.

"He pursued his way, taking that which his horse chose, for in this he believed lay the essence of adventure"— Don Quixote

Is music... good?

Hold your horses though, have you considered if music is a good thing? For some Buddhist monks, taking part in musical activities inherently isn't good. In the suttas, music is seen as an intoxicant, something the serious practitioner should not indulge. It degrades your sensory clarity. It can thicken craving, and be used as an escape. For those whose vocation is to cultivate non-attachment and refined awareness, music is risky. Not because music has no value, but because the usual way we interact with it can be careless.

Igor Stravinsky (not a Buddhist monk) had a similar suspicion. In his autobiography he wrote:

I consider that music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all, whether a feeling, an attitude of mind, or psychological mood, a phenomenon of nature, etc. Expression has never been an inherent property of music. That is by no means the purpose of its existence. [...] When people have learned to love music for itself, when they listen with other ears, their enjoyment will be of a far higher and more potent order, and they will be able to judge it on a higher plane and realize its intrinsic value.

What he meant, I think, was this: there's the music, and then there's the story you tell yourself about the music. These are not the same thing.

It's a useful distinction, which I will now explain badly. Some of what happens when you hear music is intrinsic. It's in the sounds. The way a melody rises and falls, or the way a chord resolves or doesn't. Form. Structure. Tension and release. The rest is extrinsic. You heard this song when you were fourteen and the world was a door that hadn't opened yet. This song is about heartbreak. This song got you through something. Some music seems to lean more on the extrinsinc (pop), and some more on the intrinsic (classical, techno).

I don't think one is better than the other and they often combine into new experiences. Sometimes extrinsic can be more dangerous because it's easier to insert brainworms. Personally, music makes me feel a great many things and I'm grateful we can perceive it. I would like to understanding it better. I would like better maps. And I would like to dance all the while.

The abstract quality of music

Why does music have this power? Why is it, of all the arts, the most reliable vehicle for moving through feeling-space?

It's because music is not about anything. It does not point at experience from the outside. It is the experience. The closer an artwork sits to the object rather than the perception, the harder it becomes to trade in pure feeling. A painting of grief gives you an image to interpret. A poem about grief gives you words to process. Music can simply be grief-shaped.

That's why some painters like Rothko abandon representation and move to more and more abstract art throughout their lives. Abstraction is where the feeling lives undiluted. It's also why words are trickier to convey feelings. Words want to mean things. They're stubborn that way. Poets have to break words a little, make them stop pointing and start humming. This is hard to do. It often doesn't work. Music starts where poetry is still trying to arrive.

Kierkegaard–or rather Kierkegaard's pseudonymous aesthete "A", and the pseudonym thing matters but we don't have time for it here–said in Either/Or :

The most abstract idea conceivable is sensuousness in its innermost essential character. But in what medium is this idea expressible? Solely in music. It cannot be expressed in sculpture, for it is a sort of inner qualification of inwardness; nor in painting, for it cannot be apprehended in precise outlines; it is an energy, a storm, impatience, passion, and so on, in all their lyrical quality, yet so that it does not exist in one moment but in a succession of moments, for if it existed in a single moment, it could be modeled or painted. The fact that it exists in a succession of moments expresses its epic character, but still it is not epic in the stricter sense, for it has not yet advanced to words, but moves always in an immediacy. Hence it cannot be represented in poetry. The only medium which can express it is music. Music has, namely, an element of time in itself, but it does not take place in time except in an unessential sense. The historical process in time it cannot express.

He's saying: music is the articulation of inner, temporal, pre-conceptual feeling that never hardens into concrete "this is specifically the feeling of grief about X" or "this is a narrative concerning Y". It's feeling before it becomes about.

Oliver Sacks, approaching the same question from a clinical angle in his study of music and the brain, wrote that music, "uniquely among the arts, is both completely abstract and profoundly emotional. It has no power to represent anything particular or external, but it has a unique power to express inner states or feelings. Music can pierce the heart directly; it needs no mediation. One does not have to know anything about Dido and Aeneas to be moved by her lament for him; anyone who has ever lost someone knows what Dido is expressing."

So there you go. Music points at nothing. And because it points at nothing, it can be everything it makes you feel. It can be nothing but the experience it creates.

Language and music

Language, at its best, is a transparent medium. When language works, you do not notice the tongue moving, the air vibrating, the letters on the page. You pass through the sensuous surface and arrive at meaning. Chuang Tzu knew this:

However, language has limits. Flaubert, in Madame Bovary, offered the bitter comparison:

Human speech is like a cracked kettle on which we tap crude rhythms for bears to dance to, while we long to make music that will melt the stars.

Music speaks what language cannot. It does not develop the way thought develops. It does not argue or explain. Kierkegaard says it "storms uninterruptedly forward as if in a single breath." If you wanted to characterize this quality by a single predicate, he wrote, you would say: it sounds.

When language fails, music succeeds. Leonard Bernstein noted that music "can name the unnameable and communicate the unknowable". When music works completely, when you're at star melting level, you get something like what T. S. Eliot tried to describe:

Music heard so deeply

That it is not heard at all, but you are the music

While the music lasts.

The transparent medium of language lets you forget the words and keep the meaning. The opaque medium of music lets you forget yourself and become the sound. The sound continues, fully present, while you vanish into a region of feeling-space you could not have reached by any other path.

II: Waves we Ride

It's odd that we have devoted large parts of our neural circuits to produce and process music and other arts. Language makes obvious sense. Language lets you say "Hey, there's a predator behind you" or "Don't eat those berries, Gary died from eating those berries" or "I know we've never met but I have resources and would like to exchange them for mating opportunities". But music? Why would evolution build expensive circuitry for organized sound that refers to nothing?

There's a theory that it helped us not get eaten as a defence system against predators. Another suggests it facilitated cooperation among unrelated specialists. What we can say is that there seems to have been music since there has been people.

Surprisingly, it's not a universal human feature. Some people can't perceive music as music. There's a man, according to Oliver Sacks, who can recognize exactly one piece of music: the French national anthem. There's deaf people of course, but they can feel the vibrations, and they sometimes use tactile audio systems like vests or chairs. Music is multimodal in this way. If you've experienced feeling the bass through your body you know it feels pretty good. Seeing visuals that move with the music feels good too.

Whatever music is for, one thing it does reliably is bring people together. I realize this sounds like something you'd find on a motivational poster in a middle school band room, right next to a picture of some kid with a trombone and the word HARMONY, but stay with me here. Whether it's making it collaboratively, specific songs becoming identity markers for entire nations, concerts like Live Aid, the Stand by me thing... You can listen to music from cultures you know nothing about, music in languages you don't speak, music made by people whose entire worldview and daily existence bears essentially no resemblance to yours, and you can like it, and you can feel something, and in that feeling is a kind of knowledge of those other people.

On November 22, 1963, hours after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Leonard Bernstein did not call for revenge. He called for music:

This sorrow and rage will not inflame us to seek retribution; rather they will inflame our art. Our music will never again be quite the same. This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.

Tolstoy had a theory about all this. In What is art?, he said:

The destiny of art in our time is to transmit from the realm of reason to the realm of feeling the truth that well-being for men consists in being united together, and to set up, in place of the existing reign of force, that kingdom of God, i.e. of love, which we all recognise to be the highest aim of human life.

What Leo "Bob Marley" Tosltoy is saying here is that: music is love, man.

When we wanted to explain ourselves to the cosmos, we sent music. The Voyager Golden Record, now almost one light day (!) away from Earth, carries Bach and Beethoven, Chuck Berry and Blind Willie Johnson, Peruvian panpipes and Azerbaijani bagpipes. This is us, we said to outside-the-solar-system, please understand.

Can aliens appreciate our music? First of all can any other Earth entity appreciate it? Pliny the Elder thought dolphins loved a good water-organ concert. We have since learned that most animals don't find human music pleasant, but knowing which pitches and tempos an animal's auditory system is optimized to pay attention to, we've been able to adapt human music to get animals to prefer it over silence.

The argument laid out in Principia Qualia is that music is suspiciously pleasurable. It shouldn't feel this good from an evolutionary psychology standpoint. As Michael Johnson points out, this difference might be coming from "some pattern 'directly hacking into' the mental pattern which produces pleasure/pain". His theory is that music "hacks" valence (pain and pleasure scale) partly because it is highly patterned (symmetrical).

Now, as much as music is pleasurable, auditory dissonance is notably unpleasant. Johnson notes that pleasurable music tends to have elegant geometric structure, that consonance is a primary factor in which sounds are pleasant vs unpleasant in 2- and 4-month-old infants, and that "hearing two of our favorite songs at once doesn't feel better than just one; instead, it feels significantly worse".

He concludes that "Music is a particularly interesting case study by which to pick apart the information-theoretic aspects of valence, and it seems plausible that evolution may have piggybacked on some fundamental law of qualia to produce the human preference for music." This is more obscured with extrinsic leaning music and clearer with intrinsic leaning music.

But then why don't you just inject pure symmetry? Like many things we perceive, good music seems to skilfully navigate consistency and surprise, so you can be at the limit of guessing. This means getting slight positive prediction error and thus dopamine. Johnson says that "musical features which add mathematical variations or imperfections to the structure of music – e.g., syncopated rhythms, vocal burrs, etc – seem to make music more addictive and allows us to find long-term pleasure in listening to it, by hacking the mechanic(s) by which the brain implements boredom".

Musical embodiment

There are particular altered states of consciousness that music can enable. Tarab, in the Arabic tradition, names the particular ecstasy that arises when performer and listener become so entangled that the boundary dissolves. This dissolution also occurs in flow states. If you've ever had the wait-what-time-is-it-how-long-was-I-in-there feeling, then you see what I mean. This shows up on dance floors, where, as the waking life storytellers put it, "The club becomes a temple of Aion – eternal time, unshackled from sequence, where the ego's petty ticketty tocking gives way to something older, wilder. Carl Jung knew this. The ravers know it too." Music is temporal yet out of time.

I relate it back–and this may not be super epistemically sound–to something the anthropologist E. Richard Sorenson calls liminal awareness. It's different from the Freudian subliminal stuff (repressed, buried, inaccessible) and also different from supraliminal awareness (the metacognitive you-watching-yourself-have-an-experience thing). It's when attention stays immersed in immediate, shared sensory experience. Sorenson describes it this way:

Where consciousness is focused within a flux of ongoing sentient awareness, experience cannot be clearly subdivided into separable components. With no clear elements to which logic can be applied, experience remains immune to syntax and formal logic within a kaleidoscopic sanctuary of non-discreteness.

Non-discreteness is a nice word for what happens during a good jam session, or anytime you're deep in the music.

Dancing is one way of integrating music into the world. Some neuroscientists will tell you the brain was made for movement, like Daniel Wolpert who says, "We have a brain for one reason and one reason only – that's to produce adaptable and complex movements. Movement is the only way we have affecting the world around us." We're like sonic puppets, and some people can get super close to a pure kinematic representation of the music.

Music's circuit can integrate back into reality and terminate in the muscles, the joints, the sweat.

Functional music resonance

A property of humans is that you can listen to music and do something else. I can have two sensory streams loaded up. It can trigger transitions to do work or sports and helps with flow state, especially when writing code in my experience. I surf on music almost all the time, except when I want to think-think or meditate. Then I need silence, which John Cage would say is its own kind of music.

Which brings us to the whole sprawling genus of background music. Your piano ambient. Your alpha-wave drone. Lo-fi was basically engineered to fill this need. For Glenn McDonald, a lot of it is bad because "passive listening to music whose indistinguishability is its aesthetic rationale is never going to be better than a small-prize lottery". But he agrees that this is true in every genre. "There's also genuinely inspired, professionally produced music whose express purpose is mood adjustment.[...] It is functional music, and in some sense this is opposed to artistic music, but not necessarily at its expense." Some artistic music also happens to be functional: your minimal techno, your two hour house DJ sets.

Functional music is an experience navigation tool that's been integrated in your action space, expanding the contexts in which music can serve you. You can think of it as energy conservation, but it feels more like resonance; music that makes your body recruit more energy towards X or Y. If the brain is a prediction machine, maybe background music is a way of biasing the predictions. The music becomes a kind of scaffolding for state.

Actuator waves

There's a view that consciousness is something the universe does when matter arranges itself in certain ways. It didn't start with us and it won't end with us. As Nick says, electric eels didn't invent electricity, they just figured out how to use it. Migratory birds didn't invent the magnetic field. Maybe brains didn't invent experience. Maybe they just tuned into it, like an antenna finding a signal. And if music is a way of moving through feeling-space, then perhaps the capacity for musical experience is not uniquely human. Maybe the waves will look a bit different, but there might be shared properties.

Waves other than music can affect you. For exemple tFUS (transcranial focused ultrasound) targeted at the brain can help with chronic pain or reducing tremor, but also activating visual circuits and smelling things ? It's in the neighborhood of sound-as-experience-modifier. A lot of the universe is made of waves, so it makes sense that we can affect things with waves.

Is there an equivalent of music for AI? What is the music for LLMs, if there is one at all? Prompting feels more like language than like music. It is referential, semantic, explicit. Music works precisely because it bypasses the semantic layer. Is there a way to provide structure-without-content to a language model? A kind of input that shapes the distribution of outputs without specifying what those outputs should be?

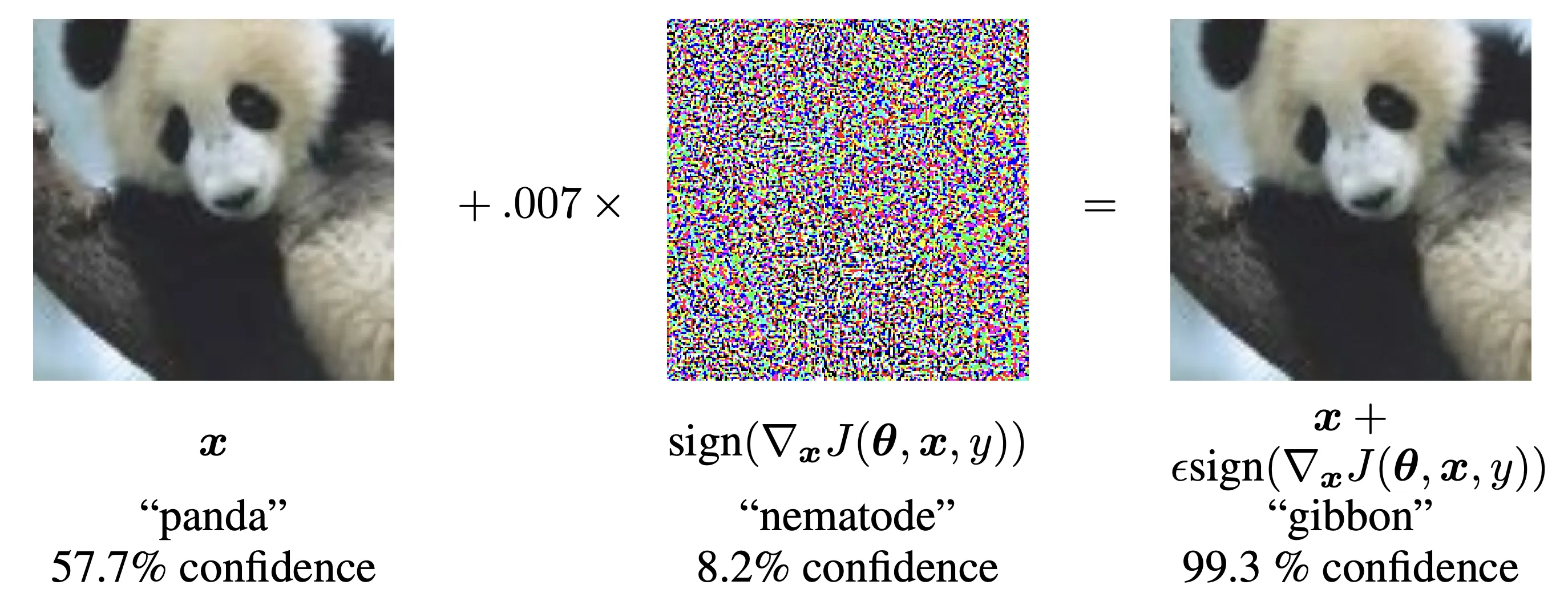

You have different input streams with knobs that can be influenced at different levels of the model pipeline. The input, the activations, the weights during generation, the temperature, quantization. You can tune activations up and down that correspond to "honesty" or "creativity" or "golden gate" without saying anything about it in the prompt, and the model's outputs shift. Also, jailbreaking or adversarial attacks seem to use the input structure to confuse the semantic load.

You could add interference during matrix multiplication. Or maybe literally acoustic vibrations on the GPU could affect the output in a certain setting? Waves adapted to the model's auditory capacity, whatever that means.

I wonder if any of it feels like anything.

III: The shape of Music

From the first flute, we've wanted to push the boundaries of music making. Breaking away from voice was one of the first transhumanist act in a way. We've built affordances that we could interact with, centered around the human body and our 3D action space. We built things our hands could hold and our lungs could blow into and our fingers could dance across, which in retrospect seems obvious but is actually a profound constraint on the space of possible instruments. We made many variations of them, even very niche ones. Glenn Gould's father sawed the legs down of a battered folding chair so he could pull down on the keys rather than strike them from above, to have a better detached (non-legato) sound, perfect for Bach.

It's been 100 years since The Art of Noises was written by composer Luigi Russolo. He was tired of existing instruments:

Who can hope to discover any new emotions in these instruments? The only emotion that they can still produce is that of widening the mouth-into an inevitable yawn! And the yawn is not exactly the newest of emotions.

In the 60s we discovered the sound of the future. John Chowning discovered timbres never before heard in nature with the FM synthesizer. Using soundwave math, deterministic reproducible sound.

We played with musical properties. One of Stokowski's obsessions was literally to make things louder. He reported, "We have amplified the orchestra six and a half times. That led to a new horizon. Of course, we shall be able to amplify more than that".

We chased new horizons in sonic variety and made so many different kinds of music. Glenn McDonald wanted to document all the different genres and subgenres, and he built Every Noise at Once in this spirit of music exploration.

The composer-performer dyad

One way to explore is to create music yourself. Of course you're never really creating. Robert Schumann put it this way: "in order to compose, all you need to do is remember a tune no one has thought of." If you've ever made something creative (it can be a song or a funky sandwich) you may know what he means though. It does feel less like construction and more like the universe is going through you. You're striving for an ideal and it merges with your own individuality and you use parts from everything you are and everything you've seen. Which on the positive side means you can never really fail at being you since it has to go through you.

But one of the pitfalls of you as a slow-changing, information-propagating, entropy-resisting system is that you might stay too close to your priors and not update them a whole lot. To get out of this, John Cage, in 1985, used chance composition where "the answers, instead of coming from my likes and dislikes, come from chance operations, and that has the effect of opening me to possibilities that I hadn't considered". Elegant in theory but also incredibly inefficient as you're left with a lot of music that sounds like a xylophone dropped down a stairwell.

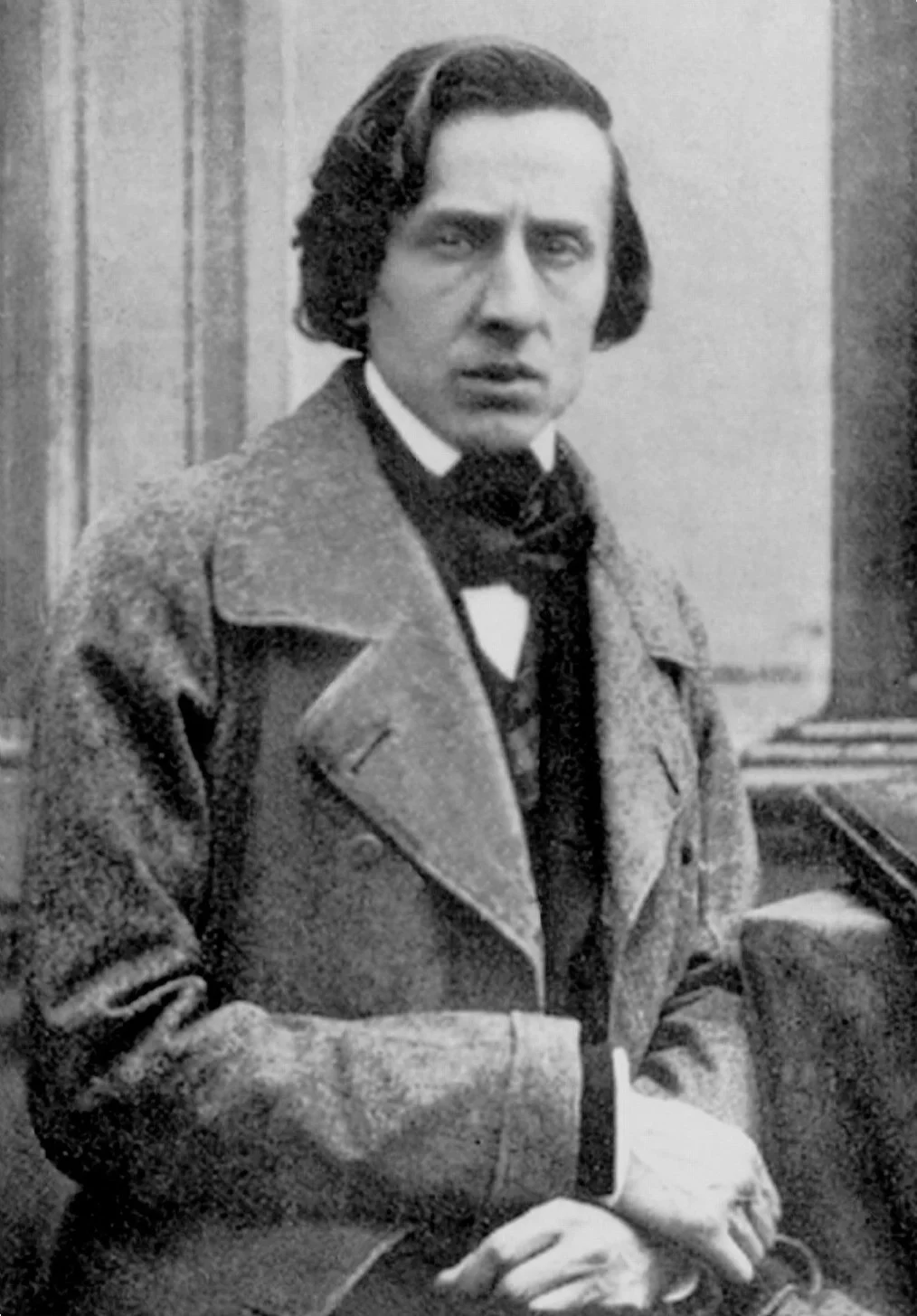

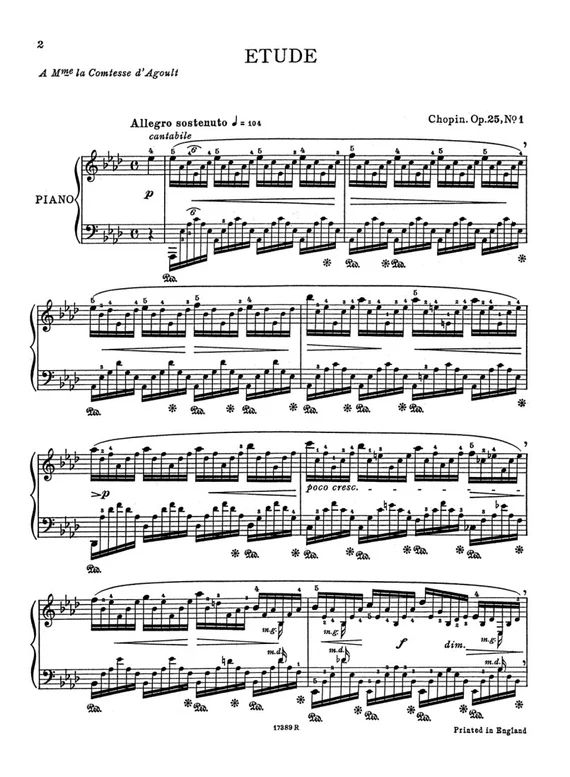

Once you've created the music, there are many cases where someone else will play it later. You're trying to write down the feeling so that another person can see some symbols and spawn it in another place and time. It's a hard communication exercise. Ferrucio Busoni said "Notation, the writing out of compositions, is primarily an ingenious expedient for catching an inspiration, with the purpose of exploiting it later. But notation is to improvisation as the portrait to the living model. It is for the interpreter to resolve the rigidity of the signs into the primitive emotion". It's like a VAE for feeling reconstruction.

It's hard for the composer to get his idea played like he had it in mind. Compression is lossy and you're limited by what you can write down. Stokowski said that "we have possibilities in sound which no man knows how to write on paper". Some composers added additional detail on their music sheet, outside of the classic score, to try and express more. Erik Satie wrote a whole string of more or less figurative precisions. Some related to the music, some to explain the context or change the player's mood. Here is my curated collection:

Erik Satie Sheet Music Annotation

Click on the music sheet for the translation.

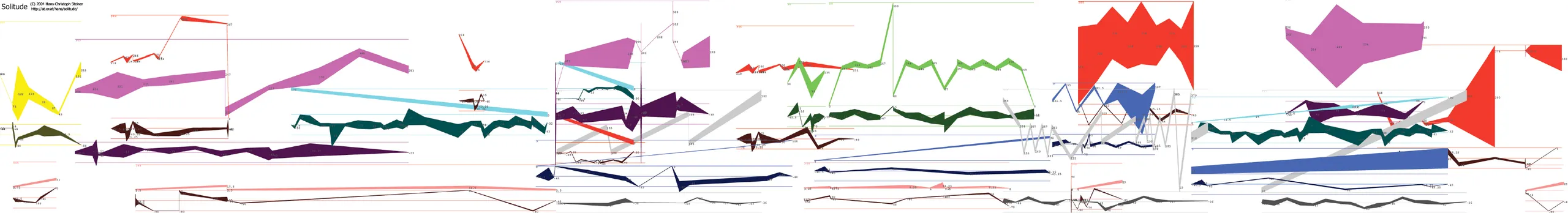

Some people also tried to escape the conventional notation:

The player then interprets the score with two tasks, which as per Jeremy Denk: "one is to do what's written in the score—incredibly important; and the other, even more important, is to find everything that's not". In a way, the vagueness is also a feature. The score leaves room for the performer's nervous system to enter the circuit. They can make the piece better or worse or different. They can adapt it for the situation and time in which they're playing. The point is that music doesn't exist on the sheet music except in symbolic form, music really exists only when it is being played and heard. When the performance stops, the music is gone.

This makes performers interesting characters because for a brief moment they are both the creator and the listener, and they can take us along. Consider Benjamin Zander, the conductor, working with a cellist. He says, "Your playing is only a vehicle to the heart, it is a roadway to the heart, it is not the heart itself. [...] Will you give us access to our heart?". Or consider Vic Wooten, the bassist, showing us that it's not about the notes or the instrument:

chromatic scale only

wrong notes only

right notes, wrong feel

Hover to Listen

Once again, the music is the feeling, and the feeling is the point. He's navigating at the feel level disregarding the operational rigidity. He can't describe this feel precisely, I'm not sure he knows what it is, but he definitely knows if it's there. These musicians are instant generator-verifiers. They can check each moment: Is this it? Does this take us there? If not, they play the next bit so that it does.

Now we can record electronic music as it's created and play it the exact same way without decoding loss. Instead, the DJ takes the place of the performer, and it stops being about a specific piece and becomes an experience-inducing timespan made of multiple compositions.

And so I'm wondering–and this is where I've been going–whether we can map this feeling-space explicitly, and stop using proxies to steer. How many distinct "feels" are there? How much have we visited? Have we felt even 1% of what is possible with music? We've made a lot of music, but so little compared to the possibilities. Every day, people post ~100,000 songs to Spotify. And yet, what's the probability that any discrete, already-existing song (assuming you can find it) happens to deliver the maximally activating emotional payload at a specific moment? I'm sure Shine on You Crazy Diamond can be some sort of local maxima in a certain context, but most likely there's even better.

Being the listener

We're the beneficiary of a century-plus of recorded sound, all of it theoretically accessible. As the listener, we're operating in the existing-music space and not the preliminary creation space. We can listen to whatever we want, wherever we want, or can we? With streaming platforms you can explore and are only limited by time in theory. You can use content based filtering or collaborative filtering or a combination of both. You can follow a high taste musical digger, or use tools like gnoosic or rateyourmusic or start from an artist and spiral outward from the starting point. But ultimately these are still based on handcrafted features, and your treasure-finding power is limited.

The territory is larger than any map though. Sometimes you randomly stumble on some things that you wouldn't have expected to hit. I spent a couple weeks outside a cyberpunk club which at this time of my life was an excellent place to be.

But exploration has a competitor, exploitation. Familiarity is warm bathwater. It is pleasurable, it brings back good memories. Your musical taste is mostly set in your teens, and the diversity of what you listen to tends to shrink as you age. Only 27% of streamed music is recent. The music industry noticed this, of course. One producer, working with The Strokes, reportedly tested audiences with a battery of questions to predict which tracks would sell. The question with the most predictive power was not "Which of these is most original?" or "Which moved you most?". It was: "Which of these bands sounds the most like something you have heard?".

The recommendation algorithms learned this lesson alright. Streaming platforms are optimized for engagement, and engagement follows the path of least resistance. For Glenn McDonald, things like the Chill Vibes playlist, in aggregate, "begin to reduce increasing fractions of your life to choosing among the manipulatively limited options offered by automated systems dedicated to their own purposes instead of yours". Or delightfully put:

He adds, "We need tools that not only reduce our isolation and passivity, but conduct our curious energy and help us recognize opportunities for discovery and joy". The playlist is not a tool for exploration, it is a tool for retention. It does not want you to discover something that might unsettle you. It wants you to keep streaming. His antidote is not asceticism though, he does not say: reject the platforms, return to vinyl, purify yourself. "You don't have to listen to any of these things. Even the most draconian free tiers, with their shuffle rules and limited skips, only regulate how readily you can get exactly what you want. But you have infinite power to outwit them, because you can want anything".

So you get this strange inversion where the more total your access to existing human music becomes, the less "human" the whole thing feels. The feeds and radios and algorithmic radios of radios compress millions of sweating, practicing primates into a smooth, scrollable feed of content that you can like or skip without ever touching the fact that an actual person once staked a piece of their life on this chorus. Authorship starts to look modular and swappable and you wonder if it's possible to imagine a version of the same feed where the slot labeled artist disappears.

IV: The state of the Art

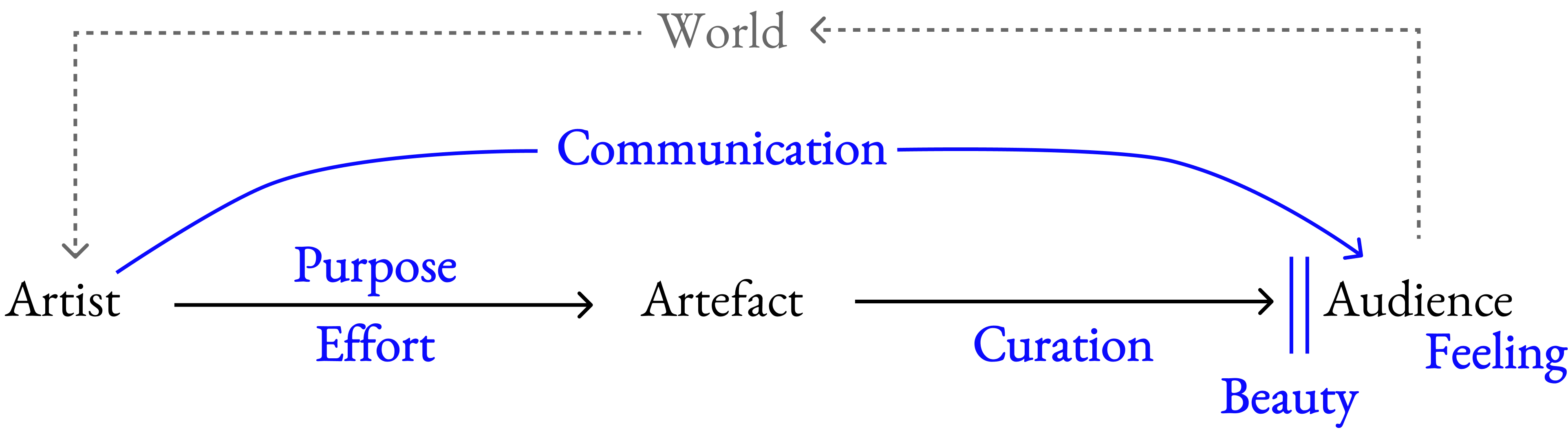

What art is or is not has been examined and debated countless times (Fountain by Marcel Duchamp to name just one example). However, it seems that the refutation of AI art comes once again from a disagreement over art's purpose: "Is it trying to communicate something?" versus "Does it evoke a feeling in the audience?".

by Marcel Duchamp to name just one example). However, it seems that the refutation of AI art comes once again from a disagreement over art's purpose: "Is it trying to communicate something?" versus "Does it evoke a feeling in the audience?".

Why is AI art controversial

The problems people have with AI art seem to exist within the following categories:

- 1) People use art to update their world model about other humans; AI art is a phony update.

- 2) It's copying/theft; copyright and money.

- 3) AI art is ugly/bad, or it can't be creative.

- 4) It feels effortless whereas we have to put in the work. You need effort to get good things.

- 5) It's a big hit to the sense of identity of artists.

- 6) AI making better art than us or more easily will lead to less human made art.

- 7) People hold on to things a lot.

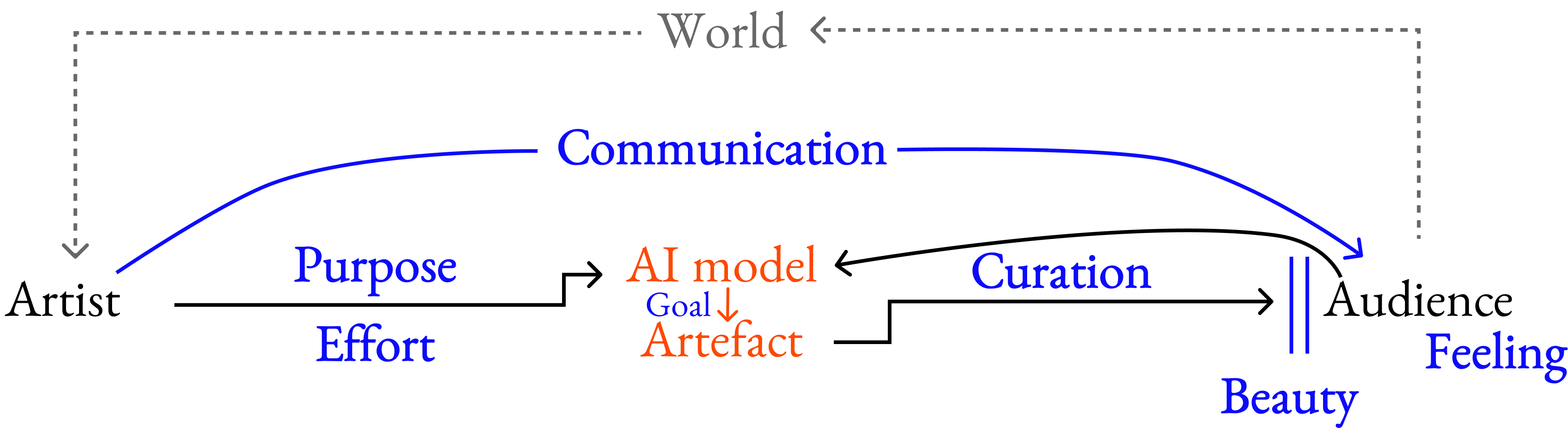

Here is how I understand the complete art pipeline:

Let's map the problem categories on this simplified representation:

The problems seem to mostly reside in the region associated with purpose, effort, and communication. In other words: the meaning associated with the artist's journey.

Art without meaning

Erik Hoel said AI art isn't art because you need human consciousness. He quotes Tolstoy too who said "the aim of works of art is to infect people with the emotion the artist has experienced". If you see art like this, as abstract communication, then as the audience you expect the emotion you're feeling to act as a bridge to the artist's own experience. This connection allows you to better understand the artist, and humanity as well. If AI takes the place of the artist, it makes sense that you'd feel cheated: your world model update was not based on a human mind's output. More specifically, if I put my Michael Levin glasses on, we don't know if AI has compassion, or if it cares about what we care about. AI doesn't face the same existential battles that we do (autopoietic self-construction, an impermanent fluid self, limitations that drive and constrain actions, etc.)

Our belief about the artist's intention can shape our experience of the art. The choices in the creative process can make the output more engaging and meaningful. This is also why there was so much morbid curiosity around who the Daft Punk really were. Where does the music come from? What's the life context of these people within which they are making this music?

Sometimes you don't read the little panels next to the paintings though. I'm pretty sure some art pieces don't have profound meaning or origin story, or that the original narrative changed and deviated to what is currently accepted.

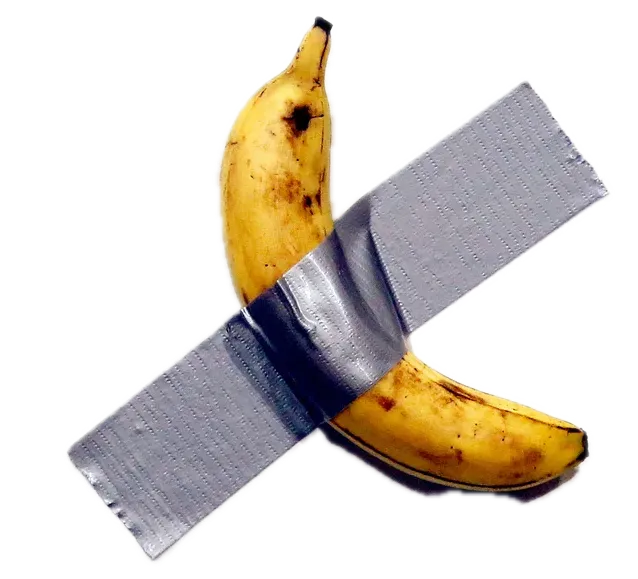

Sometimes the lack of meaning is the point, when you tape a banana to a wall  for example. If you think that's art, then we don't need meaning and you shouldn't refute AI art on this basis.

for example. If you think that's art, then we don't need meaning and you shouldn't refute AI art on this basis.

Art without effort

An artist choosing to spend a portion of their limited life on a piece is a temporal sacrifice. The time it takes is part of the artist's journey and adds to the story a certain "I know how he did this and that's impressive because it takes a long time". And with enough time, the person acquires skills that sometimes make you say "I don't even know how he did this".

This is also tied to scarcity. If something is hard to create, then it can be rare and valuable. If AI had only created a single image since the beginning, we'd consider it special and meaningful because it is the only one.

In comparison, how do you measure the effort an AI model is doing? It's hard to say if AI makes sacrifices as it is not alive and doesn't operate on the same time horizon as us. Is it hard for the AI to make this song? It did train for it. For humans, using AI tools is not considered effortful because it's possible to get a seemingly complicated complete piece very fast by typing a sentence in a box. In comparison, Ableton looks like a professional tool that requires real skills and mastery. You can vibe-art like you can vibe-code, and in the same way you can lose granular control and understanding. You can also spend a ton of time and effort using AI tools to make a piece.

It's just copying, not even good copying

Models are not copying the art they were trained with. They learn the distribution of this art and can produce outputs that look similar. Humans do a similar thing, they are inspired and built on top of each other already, and everything is a remix. If you produce a piece that already exists, that's copying. If you start from a piece and move 10% away in the latent space, is that copying? What about 50%? What about if you go as far as possible? Where is the line?

A lot of AI art is bad. One trend is that as models improve, the quality seems to go up. The great AI music I've heard was heavily processed and not created end-to-end. If you use off the shelf models, you get music with six fingers. There's often a weird sound artefact, and the details and temporal schemes don't make sense. This will change. As AI gets better at pattern recognition, it will get better at interpolating between them and producing outputs that feel more coherent, original, and "new".

Some people say AI cannot be creative because it can only interpolate within its training data. 1) Even if it can only interpolate, there's a lot of space left for new music in the convex hull of human creation, and 2) with reinforcement learning we might not be limited to the training data distribution.

AI's goal

For most of history, we've assumed that all meaningful knowledge or creative output can only come from two places: nature, and humans. But if AI can be creative, then there's now a third source: things created by our creations.

We're still getting used to the idea that intelligence doesn't just mean human intelligence. I like Michael Levin's perspective on this. Whenever we figure out how something works, we tend to say that it's just physics and not real cognition, as if it had to be mysterious. In the past, we only saw two options: a human-like mind, or just physics. A continuum view is more useful: different systems can have different degrees and kinds of cognition. That means AI doesn't have to be either "machines with zero cognition" or "fully like us".

Although AI doesn't have a clear overarching artistic purpose, it has the goal to create something similar to the training distribution. And, if we follow Michael's sorting algorithm paper's point , we shouldn't assume we fully understand what the AI models are doing. Focusing on the music might be a red herring, because that's the part we explicitly asked the model to produce. What else is the model doing that we are not good at noticing?

Humans have a natural capacity to pursue outward-facing goals that improve the well-being of others. That seems like a good direction of optimization for LLMs as well. They can improve the world through increasing the economic throughput or something, but also through direct interaction with us. The evaluation of "can it make me feel something" is an interesting one. They would have to understand us in a way. If they can create things which can engage our feelings, which can make us relate to our own deep questions, well, that seems unambiguously good.

AI can make us feel

If something exists in the spectrum which we're sensitive to, we can get feelings. This is not physically prohibited. If AI can learn what it is we're sensitive to with enough accuracy to keep it up without us realising the "faking", there's no reason it shouldn't work. If a melody moves you, and then you discover it was generated by a machine, you shouldn't revise your sensuous experience downward. The term "art" might be contentious because you can argue whether it lacks meaning, but for now simply let it be beautiful in the same intentionless way the mountains are.

I think of beauty as an absolute necessity. I don't think it's a privilege or an indulgence, it's not even a quest. I think it's almost like knowledge, which is to say, it's what we were born for. I think finding, incorporating and then representing beauty is what humans do. With or without authorities telling us what it is, I think it would exist in any case.

— Toni Morrison

Increasing the amount of beauty in the world is a worthy endeavor we often neglect. For beauty is what exists at the intersection of perception, and feeling is what makes this intersection matter. I don't experience the movie Grave of the Fireflies as "beautiful", I experience it as "devastating". People are making things with AI that give me the early embryos of feeling, including some that tingle differently. I believe it will eventually be able to evoke emotions as powerfully as Takahata's movie. And perhaps it will be more powerful, and everyone will weep and smile and gaze with awe.

If AI can make art that blossoms human emotions, it might also make us feel closer to it. The history-textbook trajectory of AI may partly depend on whether, along the way, AI produces art that people resonate with. I hope it will increase compassion. Humans and AI–and many other things–part of the universe playing a song for itself. Using humans using instruments using physics. Or using humans using AI using physics in a different way. Nothing separating creator from creation from creation's creation.

AI enabling communication

AI can support the music production process of an artist as a tool, much like existing instruments, serving the artist's purpose. Without purpose there is no art.

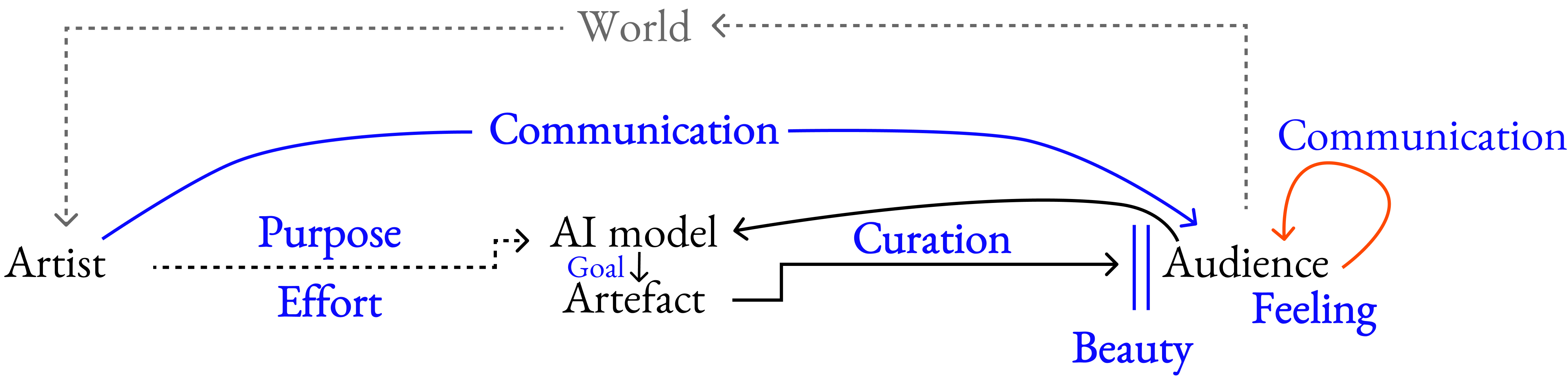

Meanwhile, we're heading towards a paradigm where models can move the audience without an artist operator apart from the one who originally created the model. In this case, making models that make art is the artistic creation itself. The act of training models on curated data with the goal of eliciting certain feelings is the new artistic journey. Everything the model communicates downstream is part of the original meaningful modeler purpose, who wanted to share something with the audience. The audience can interact with the model directly, and art starts to look like this:

You cannot outsource your own taste though. The audience will inevitably become more involved until it becomes the artist. AI can enable this by automatically surfacing your emotional latents through feedback loops like RL or later with Neuralink type stuff.

Music created from your own sensibilities. A way to know yourself better, and by sharing this music with others they might understand you more too.

Change is hard

In 1906, the composer John Philip Sousa published an essay called The Menace of Mechanical Music. He foresaw disaster. The phonograph would kill music. People would stop playing instruments. The living art would become a dead commodity. I feel like people are once again rewriting this essay these days.

Unfortunately, your brain plasticity freezes. You live in a static world. You've not built the synapses that meta learn on the activations. And so change doesn't hit right.

For artists, it can unsettle their sense of who they are, and that's entirely understandable. The advent of AI art doesn't mean we should stop having consideration and empathy for them. Part of it is also due to being able to make a living, and that's when the copyright question comes up. The real problem, as Jordi Pons puts it, "is on training data, specifically whether training AI models using copyrighted materials without permission qualifies as fair use". I'd argue that copyright is outdated and needs to change, and I won't dive into it but here are some perspectives. Things are moving though and the labels have started to make deals. In the long term, there's probably financial interest in being able to explore feelings efficiently and sharing valuable feeling-enabling pieces.

Integration of AI in the world

As the audience becomes the artist, the real burden of effort falls on consumption. Children like "Baby Shark" but adults appreciate both Rachmaninoff, Tuvan Throat Singing, progressive psytrance, and the knotted polyrhythms of Congolese soukous, right? We've seen that's not really the case. But do you actually deserve more? For some people who want a constant stream of slightly different background piano or electro, infinite medium quality music solves their problem. Just a little bit of prediction error to get that dopamine hit and not get bored. No need for good music there.

AI art is like anything that we can make easily. You can wear cheap clothes, or expensive tailormade ones. You can go to 3 starred restaurants, make food yourself, or eat fast food. CJ from dadabots puts it perfectly:

The feeling from ai slop is the same meaninglessness feeling scrolling though engagement-optimized clickbait thumbnails on YouTube I realize I am feeling fed a sea of crap, designed to usurp my attention, which has little nutritional value to me, biologically or psychologically, and I hate it. "humans make slop too" is the right progression of the narrative, because it leads to "why" and how do fix it? "Slop" is mainly about nutrition. When we consume it, what does it change inside of us? This is why the term is perfect across all media.

Slop as nutrition because art is an input that goes through you and evokes feelings. There is plenty of good art around, and as Glenn said, you can want anything. But yeah, that's hard when you can just get infinite things that are okayish without really thinking about it.

My hope is that we can build tools that make it easier to want better things. For example, I don't like running but I love doing team sports with another objective. In the end I run all the same and put in a lot of effort, but it doesn't feel like it. Putting effort in tools that are closer to feeling space will be more effective because you will get rewards more frequently.

Another thing worth saying: nothing is going to be better than you at being you. You can and should still play music for yourself and others. The experience of creation won't worsen, and you'll even get new tools to do new things. Making music is a way of being alive, of moving through feeling-space with your own hands. It's a way of being you. One of my favourite things in the whole world is music-ing with my friends.

Great future ahead. Also, many dangers. Flourishing is the goal.

As with all progress, the world isn't perfect today, there is a great future ahead but also many dangers. If you hold on to only one of these you won't have the full picture.

People listen to different music; the sound designer Yuri Suzuki says that a new sound model will only please max 40% of listeners. People also listen to music differently; Spotify put you in different clubs in this year's Spotify wrapped.

AI music models will be able to learn your preferences, and music can be generated specifically for you. It will be a bit tricky because whereas math and code have verifiable rewards, what metric do you use for "is this a good song?". It's not sound quality or diversity. One way is to ask people. MusicArena runs tournaments between models for performance evaluation. In Midjourney you can create a profile by selecting images you prefer. You know what you like, can we tap into the reward model stuck inside your head? More like this vibe, less like this vibe. This one's a banger. I'm not sure I know why. I don't need to know why. If you don't explicitly know what you like, maybe you could also use blink rate or pupil size. Or even easier, if you skipped a song and how long you listened to it. RLHF explores close to the distribution, but what to listen next might be far outside the distribution so you'd need to handle that somehow.

If this works, if models learn to generate music that reliably satisfies your specific desires rather than guessing at them, what happens next? One possibility: everything else starts to sound wrong, like wearing someone else's shoes.

The specific danger in this case is that we end up in a musical world with no exploration, no aesthetic risk, no deep enjoyment. Basically we create a soul sucking music TikTok, and music becomes only a solo activity. It seems less dangerous than actual TikTok because you can listen while doing other things unlike video which fills your sensory streams.

But if it's so good won't you want to put your full attention on it? Can we wirehead with music? You'd need to be consistent about getting into incredible states and no side effects where you feel bad afterwards. And I don't think you can get brainrot from music though, but maybe you can actually through the lyrics.

Yeah, let's make sure that doesn't happen. It's always about bringing it back to reality, and sharing with others. I'm hopeful, and people are building incredible things already. So much so that it makes me nostalgic about all of the beautiful music we've created up until today, and eager to taste all that we will be able to create tomorrow.

V: AI & New Affordances

We are once again in the position Stokowski described:

Now that we have great freedom and can produce almost anything we wish, what relations are desirable esthetically, musically, between the fundamental and its components? At first the music lover thinks he knows, but after he thinks about it a little he realizes that he really doesn't know. We know what we have done in the past, but now with enlarged possibilities how shall we define what is going to be those ideal relations?

His solution is that "there again the physicist, the musician, and the psychologist must come together and study the problem". The job description sounds, in retrospect, like what we might now call a qualia researcher.

We can move away from the musical archetypes we've constrained ourselves with, removing man's handcrafted features and laws. There are regions of the possibility space that human tradition has never explored just because we can't see them from where we're standing. Towards move 37s of music. Maybe we'll have the same loop for music as we have with chess and go engines where we study AI music, learn from it, recreate it and so on.

Maybe there's music that humans haven't been able to do yet, something like:

Consider what becomes possible. Franz Liszt composed a Symphony to Dante's Divine Comedy, but it contains only two movements: Inferno and Purgatorio. There is no Paradise. Richard Wagner convinced Liszt to abandon it, arguing that no earthly composer could faithfully express the joys of Paradise. I think AI can do hell and purgatory and paradise and everything in between and everything beyond. It will make the music of the spheres and the new folk music too.

AI will change the metamusic too

We can talk about music with other people as a shared cultural artefact. We both know Taylor Swift, we can sing together because we know the lyrics, and we know what she's up to and when she's coming to our city for her tour. There is a whole ecology of reference and ritual.

There's also the organizational containers: how music is packaged, distributed, consumed. These feel natural and inevitable, but they might be historical accidents.

The album and the track

We had albums because we had vinyls then CDs. Artists composed for the container. We still have albums, but the landscape contains other forms now. Playlists: themed, shared, keyed to event or periods of life. DJ mixes which have always been the native format of dance music. Curatorial acts as an artistic process in itself.

The goal once again is shaping the experience of the qualia havers while the music plays. There will probably be other forms too, we've already seen a collaborative ai album. There will be more.

The artist

Do you need an artist to appreciate music? When you listen to a DJ set, you are often hearing dozens of producers whose names you will never learn. The experience is not diminished. The music works or it doesn't. The provenance is irrelevant.

If you're into an artist that has tapped into something, you might want to hear more songs like it but their discography is limited. With LoRAs you can reproduce a band's style and make a lot of similar music, or prompt it towards other genres and create chimeras. Or maybe artists will produce as much music as possible to seed the training data so that models use it for future music creation. In the same ways writers are writing for the LLMs, you'll want to play for the music models to stay relevant.

Visuals

What do music videos mean then? Currently a marketing device, or a narrative interpretation. We can build new visual experiences. Maybe some visuals might even give us new insights into what's going on in the music.

Hardware

As our use of music changes, so should the machinery. I keep hearing people say they want a device that does only one thing: play music. Bluetooth, internet connectivity, access to a streaming platform, and nothing else. No notifications. No email. No feed. Just sound.

On the creation side, entirely new instruments are emerging. Tools like Neutone Morpho, which use neural networks to transform sound in ways no acoustic process could achieve.

The moment

Live music has always been unrepeatable, it's part of the appeal. We're getting more opportunities for multisensory unique interactive collective time-bound unreproducible experiences. Dadabots have been doing wild stuff and leading the pack. They invented prompt jockeying and perform live generative beats .

What does the scene look like?

If you're interested in the history of AI music, I recommend Jordi's teaching material. The very short story is that we used to generate MIDI–chords and notes, symbolic representations that still required rendering into sound. Projects like FolkRNN. Now we're mostly generating full music end to end, the models output waveforms.

Musicians are at the forefront of the technology and using it in different ways. Some artists are releasing AI versions of their voice, like Grimes, or Holly Herndon.

Nao Tokui has been exploring human-AI collaboration for years. Back to back sets with AI in 2017, colabs with neutone, MusicGen-powered DJ looper etc. Google's Magenta team built Lyria which can jam with you in real time. They have released new tools to interact with music like Music FX DJ, Infinite Crate, Space DJ. There are projects empowering Southeast Asian instruments. There is an AI Song Contest.

I love to see people having fun with it. And sometimes I find stuff that really resonates with me, this AI acid album for example.

But all in all, non-musicians interested in this stuff are mostly using things like Suno (which is now impressively indistinguishable from human music). AI is very good at approximating existing stuff that is hard for humans to do, like a symphony. For now it fails at making a textbook sonata but the average listener can't hear the difference. You can also create new genres like turkish folk reggae, or put as many genres as possible in a single song.

The public is there for it too. There was some backlash in 2023 with Anna Indiana an AI singer songwriter which felt like a violation of something. But two years later, an AI-generated song has entered a Billboard radio chart for the first time. Xania Monet, created by Telisha Jones using Suno, signed a $3 million record deal.

You can also use it to tell yourself messages more or less subliminally. Nick says "i'm using it atm for messages I want to meme myself more into that i also just enjoy the sound of most songs have messages i dont want to be infected by, v rare i find one i do that i also enjoy the sound of, much easier with suno".

But text-to-song is the wrong form factor to generate truly great music because musical preferences and feelings are hard to introspect and describe in text. As Bret Victor says "I have a hard time imagining Monet saying to his canvas, 'Give me some water lilies. Make 'em impressionistic.' Or designing a building by telling all the walls where to go. Most artistic and engineering projects (at least, non-language-based ones) can't just be described."

When you read how some artists are using it, you see that what they're looking for, as expected, is granular control. Suno actually recently came out with Suno Studio for such creators.

Francis Bacon, in 1627, imagined "sound houses"–places where all sounds exist. Walking around the sound house, what do you touch, what do you pull? What happens when you do? What's the right level of abstraction?

New affordances

I'm interested in being able to reliably find a certain musical path to a feel. How do you efficiently search the music space? What would the ideal tool for this exploration even look like? What are its requirements? If we can create by listening maybe we don't need a full blown map and can just check if it feels great for us. The audience is becoming the artist, and the goal is to maximize bandwidth from taste to feeling through music.

Tolstoy considers Beethoven's ninth symphony to be bad art because it's mostly incomprehensible. He hoped that the future artist would come from the laypeople as "he will only produce art when he feels impelled to do so by an irresistible inner impulse". The elitism Tolstoy criticised may not survive the transition as anyone will be able to generate music tuned to their own experience.

The goal of making music easier to create is old. In the 17th century, Athanasius Kircher built the Arca Musarithmica, a wooden box of combinatorial tables designed to let non-musicians compose church music. The tool we build should be easy to use, as we're competing with familiar music, maybe soon in a TikTok-like format. The corollary of usability is that, as we explore, we should minimize the "negative reward" of hearing bad music so users stay motivated to keep using the tool.

Ideally, the tool should allow us to explore new regions of high amplitude feelings, surfacing sounds which may lie far from whatever happens to be playing now, and it should be better at finding them than we are. In order to opperate efficiently, we will need close proximity between the action space and the feeling space.

In order to build this, we'll probably need to focus on:

- Efficient search of the musical manifold learned during pretraining

- A scalable reward signal from human personal preferences to curate those findings

Contrary to math and code, (2) requires a lot of human data and drifts heavily in time as user preference shifts. This makes human-AI interactivity through (1) interesting to explore as a stepping-stone for (2) or for its own sake as a musical instrument.

We can summarize the requirements for our experience exploration tool:

v1.0 specs

- able to bring you to new spaces with high amplitude experiences

- limit time-to-feeling-recovery

- operate close to the feeling level

- easy to use

VI: Prototypes

So basically the idea looks something like this:

We're not quite there yet.

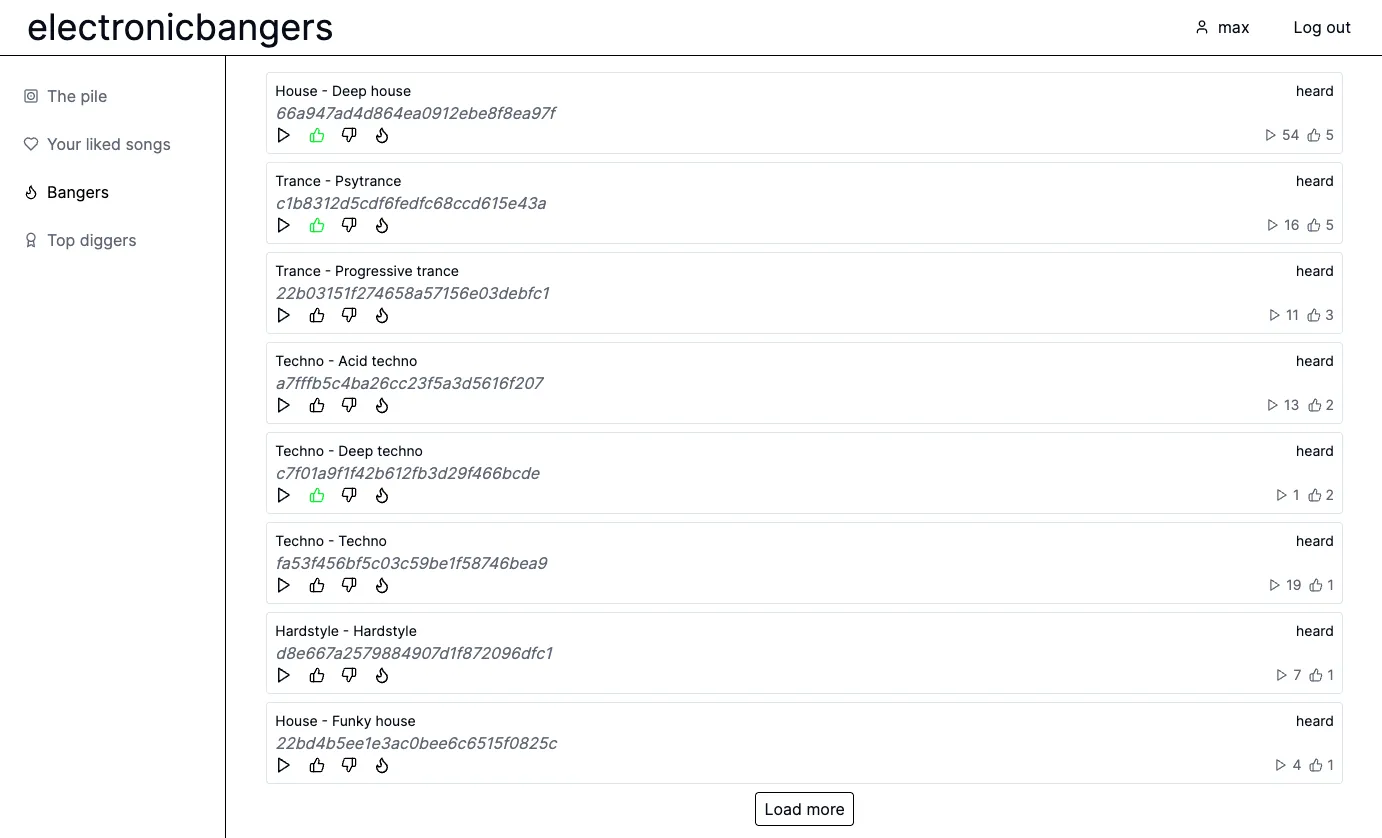

electronicbangers - Collaborative Filtering

When MusicGen came out, with my friends Aurélien and Matthieu we prompted it with thousands of electronic music variations. We put it all on a custom music streaming platform, and by liking the good sounds we surfaced them for the others.

We soon stopped using it though because so much of the pile was terrible, and the tracks only lasted for 30 seconds.

Melodjinn - A Music World Model

We recently started toying around again with AI music, with the list of requirements for efficient exploration in mind, and after Google Deepmind released Genie, a world model that can generate dynamic video worlds you can navigate in. Here's an example output:

To put it simply, Genie is an AI model that uses unlabeled videos and learns how actions can change what happens from one video frame to the next, by compressing frames into tokens and discovering its own "button presses" (latent actions). During inference, you give it a starting image and choose among these buttons, and its dynamics model predicts the next frames, turning that image into a simple, playable world you can move around in.

We thought we could do something similar for music. Consider a song as a "world" with actions and dynamics. Low-level actions might be individual notes, high-level ones can be drops, builds, and tempo changes. And there might be an even higher level where it's fully synced to a specific feel you'd like.

Matthieu did most of the technical work, and his blogpost explains how it works in more detail, I recommend you read it. To show the idea works in the simple case, we used a tiny synthetic drum world where songs can contain 3 different kinds of drum hits placed randomly. Ideally, the model will discover 1 action for each drum type, plus one for silence. And that's what it did!

You can try it below by loading the models in the browser, and pressing 1, 2, or 3 to play each learned drum.

.

Postlude

The point of the AI Sound House is "I can move through feeling with intention" like the difference between stumbling into weather and knowing how to sail.

Music is uniquely suited for this because it's already a nonverbal control surface for the inner life. As models get good enough to be responsive at the grain where taste lives, we can build portals to go into a shape of time you can inhabit. Fewer dead ends, fewer 10,000-times-then-nothing.

The culture is already mutating: live generative sets, new genres, making the act of making models into the actual art-object... On one hand, musicians using AI as a new tool that allows for previously impossible stuff. On the other, the listener becoming producer becoming curator becoming co-author of their own soundtrack.

So the mandate for the Sound House is make it exploratory, make it connective. The highest use of these affordances is adventurous contact, it's tools that enable you to like what you didn't know you could, and then make you reach for the aux cable in a room full of friends. Towards more shared aliveness.

I'll let my friend Aurélien and his band members Quentin and Pauline who are also my friends take it away from here.